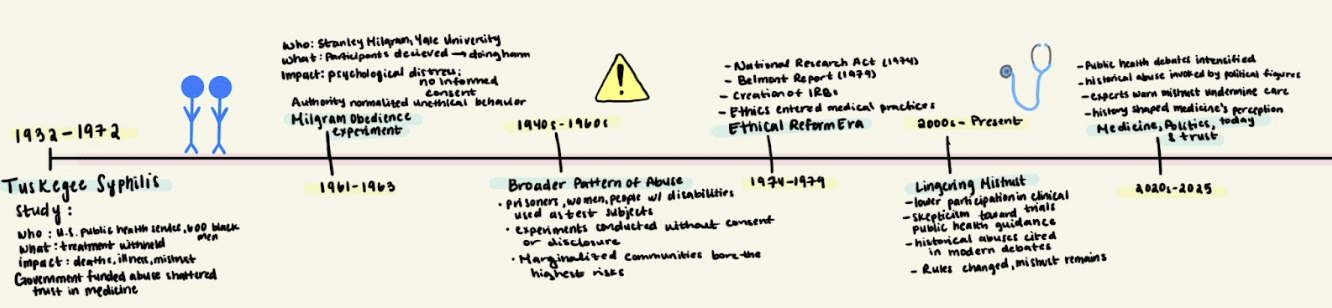

America’s unethical experiments and their lasting impact

By Prisha Garg ‘26

Graphic by Prisha Garg ‘26.

In the United States, mistrust in the medical system is often portrayed as a contemporary issue driven by misinformation, politics, or social media. But for many Americans, especially those from marginalized communities, skepticism toward medicine did not come from the internet; it came from history.

Even at Catlin, students are part of the healthcare system through vaccinations and routine medical care to some extent. Simultaneously, they encounter health information through social media and political discourse, where debates about medicine are highly visible. Understanding the history behind medical mistrust is important because it helps us separate fact from fear and think critically about the health decisions we face today.

Throughout the 20th century, doctors and researchers conducted experiments that violated basic human rights in the name of scientific progress. These studies were not hidden in fringe laboratories; they were government-funded and publicly defended.

While these abuses eventually prompted reforms such as informed consent and Institutional Review Boards, the safeguards were only built after decades of irreversible harm. Communities that were exploited lost trust in medical institutions, a legacy that continues to shape how people experience medicine in 2025.

One of the most infamous examples is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Graphic by National Archives Catalog.

Beginning in 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service recruited hundreds of Black men in Alabama, most of whom were poor sharecroppers, under the promise of free medical care. In reality, researchers withheld treatment for syphilis even after penicillin became widely available in the 1940s. According to the National Institute of Health, participants were never informed of their diagnoses, and many died or suffered severe complications as a result; the study continued for forty years.

Tuskegee was not an accident or a mistake. It was enabled by racism, power imbalances, and the belief that the pursuit of scientific knowledge justified human suffering. Researchers prioritized data over lives, assuming that the subjects’ lack of education and social power made deception acceptable.

When the study was finally exposed in 1972, public outrage forced its termination, but the harm had already been done: dozens of men had died, families were left without answers, and generations of descendants inherited a deep mistrust of doctors and government-sponsored research.

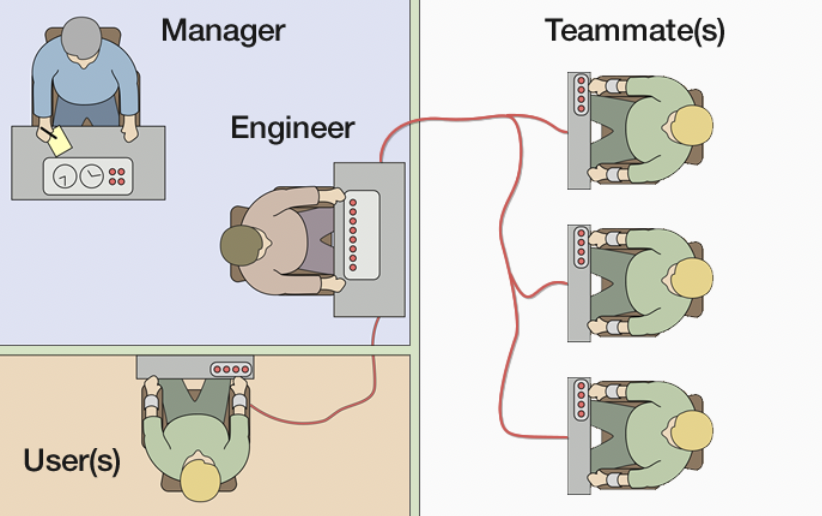

Psychological experiments also crossed ethical lines. In the early 1960s, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted obedience studies at Yale University to understand how ordinary people could commit atrocities.

Graphic by Fred the Oyster.

Participants were instructed to administer electric shocks to actors pretending to be harmed, believing they were causing real pain. Despite visible distress, they were urged to continue by authority figures in lab coats. Many participants later reported guilt, anxiety, and trauma.

While Milgram’s work offered insight into obedience and authority, it also revealed how easily ethics can be overridden when institutions normalize harm. Participants were deceived, emotionally manipulated, and denied the ability to give informed consent; standards that would be unacceptable today.

These studies contributed to the development of modern ethical standards but are not representative of all medical research. They reflected a broader culture in which authority was rarely questioned, and marginalized communities bore the greatest risks. Women, prisoners, people of color, and individuals with disabilities were frequently used as test subjects without consent.

The exposure of these abuses eventually led to reform. In the 1970s, the U.S. established Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to oversee research involving human subjects. Informed consent became a cornerstone of ethical practices, and researchers were required to justify risks and protect participants.

On paper, medicine learned from its past. But recent research shows that patients’ mistrust has not fully disappeared.

According to the Pew Research Center, a majority of Black Americans report negative experiences with doctors or the healthcare system, and many cite historical mistreatment as a reason for skepticism toward medical research. Studies published by the National Institute of Health show that awareness of experiments like Tuskegee continues to influence whether individuals participate in clinical trials or trust medical recommendations.

This mistrust has real consequences.

Lower participation in medical research leads to gaps in data, worsening health disparities. During public health crises, skepticism can translate into delayed care or refusal of treatment. In 2026, as debates over vaccines, reproductive health, and public health authority intensify, the legacy of unethical experimentation looms large.

Political rhetoric has only complicated the issue. Figures such as Robert F. Kennedy Jr., United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, have amplified distrust in medical institutions, often referencing past abuses to question current science. Kennedy states, “There’s no vaccine that is safe and effective,” during his Senate confirmation hearing while discussing vaccines and public health policy.

Under President Donald Trump, clashes between political leadership and medical experts further blurred the line between evidence and ideology.

While skepticism can be healthy, historical cases such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the Milgram obedience experiments demonstrate how easily distrust, when detached from accountability, can undermine public health. As bioethicist Dr. Harriet Washington notes, “Such research has played a pivotal role in forging the fear of medicine that helps perpetuate our nation’s racial health gulf,” underscoring the lasting impact of past abuses on attitudes toward healthcare today.

Medical ethicists argue that rebuilding trust requires more than transparency; it requires acknowledgment.

While many institutions have issued apologies for previous unethical experiments, research suggests that apologies alone may be insufficient to repair long-standing mistrust. As a research paper from Research Gate states, “Public apologies can help to repair trust…yet many of these apologies ring hollow.” Leading them to “fail[ing] morally or politically.”

Ethical responsibility today means listening to communities, diversifying research leadership, and ensuring that informed consent is meaningful rather than merely procedural.

As students and future leaders, we have a responsibility to question systems that present themselves as neutral while causing real harm. At Catlin Gabel, this means engaging honestly with history, listening to voices that have long been ignored, and holding science and medicine to ethical standards that center on people.

The story of unethical medical experimentation is not just about what happened decades ago. It is about how history lives on in hospitals and public health discussions. Modern ethical standards exist because people were harmed, and remembering that fact is essential to ensuring it never happens again.