The special stillness of slow cinema

By Andy Han ‘26

Still from Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975).

Courtesy of The New Yorker.

In 1930, the average shot in an English-language film lasted about 12 seconds. By the 1960s, it dropped to around 8 seconds. Today, it’s as low as 2.5 seconds. But why do modern movies need to move at breakneck speed, and how has it impacted viewers?

According to James Cutting, a psychologist at Cornell University who studies the evolution of cinema, “All these things are working to hold our attention better,” he said in reference to faster editing and pacing in contemporary film.

These were likely conscious decisions, partly motivated by a desire to accommodate and profit from the shorter attention spans of modern audiences. However, the mainstream film industry has continued to decline in cultural relevance and box-office revenue.

While fast-paced and action-packed mainstream movies are diminishing in popularity, recent smaller-scale and slower independent films like Chloé Zhao’s “Nomadland” (2020), Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s “Drive My Car” (2023), and Celine Song’s “Past Lives” (2023) have gained global recognition.

In response, the term “slow cinema” has reemerged to describe a film movement that directly contrasts the core ethos of big Hollywood productions, instead aligning more with the elements of arthouse film.

Despite the relative novelty of the term itself, the phenomenon of slow cinema is by no means new. The slow cinema movement has long been established since the days of filmmakers Béla Tarr, Yasujiro Ozu, Edward Yang, and Michelangelo Antonioni.

The slow cinema movement received its second wind in recent years, particularly garnering appreciation from younger audiences—hinting that viewers are growing tired of formulaic and fast-paced approaches common in big-budget blockbuster films.

But what is slow cinema, and does it address the issues posed by these modern blockbusters?

Tony Stocks, Upper School English teacher and film buff, describes slow cinema as a set of films which put “an emphasis on the long take, that de-emphasize narrative, and place a corresponding emphasis on atmosphere and mood.”

In this context, slow cinema can be classified as a sort of reactionary countermovement since it directly goes against the core tenets that most modern blockbuster productions adhere to. This contrast is most visible in how slower and faster films develop their plots.

When asked about the detriments of faster films in terms of plot development, Stocks commented that, “If everything is moving very quickly and it’s just slam-bang action for two hours, there’s a tendency to surrender to the spectacle.” As a result, these films are incredibly over-narrativized and often tell rather than show.

The opposite is true for slow cinema. Due to their often minimalistic approach to dialogue, slow films rely on visual storytelling to encourage audience engagement and interpretation—contributing to the contemplative atmosphere present in most films under the movement.

Furthermore, there are simply some special elements that faster films lack completely.

When asked about the unique benefits one can take from watching slow films that faster films cannot achieve, Stocks said that “there’s a way in which the pictures we’re talking about encourage a kind of creative, imaginative reaction in the audience.”

Adding on, Stocks outlined the conditions and consequences of said imaginative reaction. “If the images and the narrative construction are compelling enough, then I think you’re more open to becoming a contemplative audience member rather than simply one who’s surrendering to that spectacle,” said Stocks.

Given the space for contemplation, audience members have the opportunity to explore “the complexities of characters and the way they're feeling” as well as “the ramifications of the situation that they find themselves in.” Stocks also noted a shift in the audience’s role when watching slow films, and how they become co-constructors of the film’s meaning as active participants.

Although my descriptions of faster films might seem like a condemnation and rejection of all big-budget Hollywood productions or Marvel movies, it’s important to keep in mind that they aren’t inherently detrimental to younger viewers.

The one major downside to their industry dominance is that they deprive viewers of more opportunities to encounter alternative media they might enjoy. As Stocks explained when asked why people should watch slow films, “Everyone should have an opportunity to be exposed to different kinds of aesthetic strategies and aesthetic philosophies because only then can you figure out what you like,” he said.

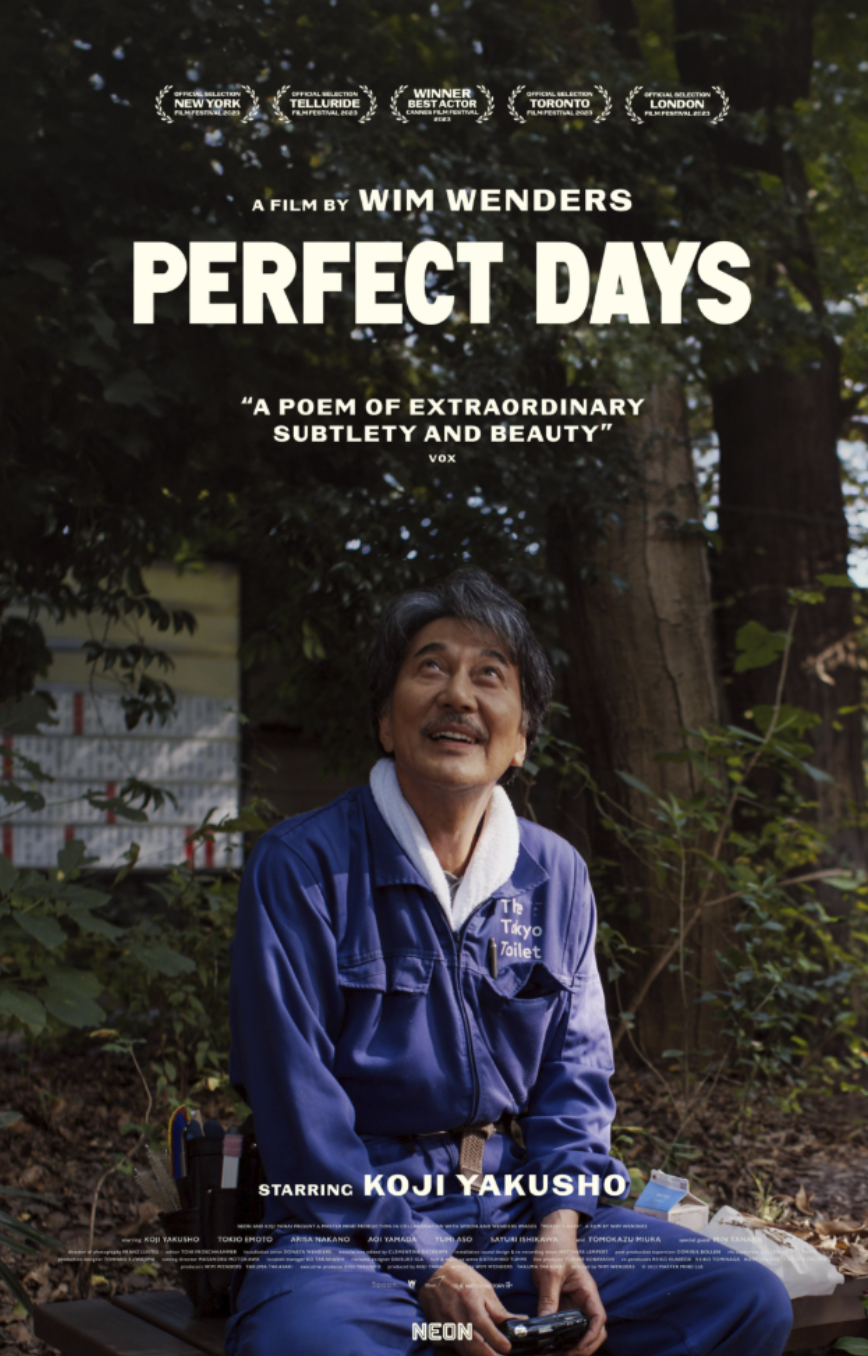

Poster for Perfect Days (2023).

Courtesy of IMDB.

Senior Krish Caulfield just happens to be one of these individuals who found joy in slow film. Caulfield was particularly a fan of Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days (2023), which follows an old Japanese man named Hirayama, a public toilet cleaner in Tokyo, as he goes about his day.

When asked why he liked this film—one which stood out starkly from his usual taste in film—Caulfield said, “This is one of those movies where when you watch it, you're just sort of like, okay, why did this just take an hour and a half or two hours? But then you wake up the next day, and you're like, oh yeah, that was a good use of my time.”

Caulfield added that the film “feels real, it feels authentic, it feels transparent,” capturing life the way an ordinary person would experience it. “But I think what's unique about this film,” he continued, “is that you become a bystander…there's more interpretation in a film like this.”

Ultimately, slow cinema offers a valuable opportunity for viewers to find the spectacle in images and stories that appear mundane, encouraging them to dig deeper and engage with a story as a co-constructor of meaning rather than someone who surrenders to the film, even if that means watching a man clean toilets for two hours.

Please click here for slow film recommendations.