OPINION: The SAT uses a gilded scale

By Evan Zhang ‘26

Graphic by Gracyn Gardner ‘26.

For millions of high school students every year, three letters loom large: SAT.

The acronym refers to the Scholastic Aptitude Test, a 98-question standardized test distributed by the College Board that aims to measure students’ proficiency in reading, writing, and math. Although over 80% of American colleges and universities have implemented test-optional admissions as of 2025, many still consider applicants’ test scores in the admissions process. Consequently, the SAT remains a source of stress for students and a trending topic for their parents and college counselors.

In fact, despite schools’ test-optional policies, attendance for the SAT has steadily risen since 2021. According to the College Board Newsroom, more than two million seniors in the class of 2025 have taken the SAT, a record high for the last five years. One major factor influencing the increase is the test’s recent transition from paper to a fully digital format.

With such high participation, it would be natural to assume that the SAT is a fair test through which students are given an equal opportunity to demonstrate their academic prowess. Unfortunately, as it turns out, that is not the case.

Not only does the SAT perpetuate wealth inequality and by consequence, racial disparities, but the College Board also prioritizes profit over student improvement. Without context, these accusations may seem jarring and unfounded. But looking at the research paints a different picture.

As outlined by the National Education Association, non-white students disproportionately receive lower scores on college admissions tests like the SAT, preventing them from the same college and scholarship opportunities as their peers. This is based on data from the National Center for Fair & Open Testing.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the SAT was briefly put on pause, and thousands of colleges went test-optional and even test-free. During this hiatus, as The Guardian notes, their applicant pools subsequently became much more diverse. “College admissions counselors saw more applications from first-generation Black and brown students when schools forwent test scores,” observed Director of DEI John Hollemon from the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

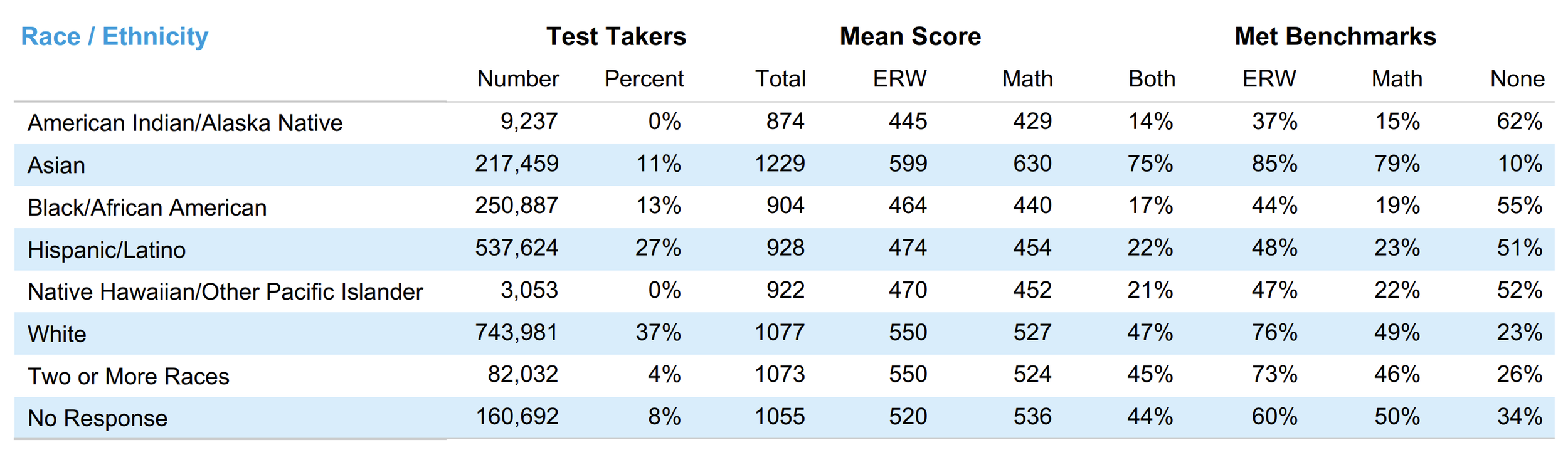

Current data on SAT scores by demographic highlights a likely cause for this hesitancy. Examining statistics released by the College Board in its 2025 SAT Suite of Assessments Annual Report, it becomes startlingly clear that there remains a strong correlation between a test-taker’s score and their race.

Note that the data below is from the class of 2025 and considers only each test-taker’s most recent score, disregarding their past scores if the test was retaken.

Table from the College Board’s 2025 SAT report displays how test takers of different races performed and whether they met key benchmarks.

Courtesy of the College Board.

On average, Asian students—who made up 11% of total test-takers—scored the highest, with a mean score of 599 on the English Reading and Writing (ERW) section, 630 on the Math section, and 1229 overall. By stark contrast, Black students—who made up 13% of test-takers—were the second lowest scoring population, with a mean 464 on ERW, 440 on Math, and 904 overall: a staggering 325 points less than their high-scoring counterparts.

American Indian and Alaska Native students, who made up less than 1% of test-takers, scored the lowest on both sections and overall, with a mean final score of 874.

This chart highlights the extreme disparities that still exist among test-takers of different racial demographics. At a glance, one might make the assumption that the SAT is inherently racist or culturally biased. However, the correlation between student performance and race is merely a symptom of a broader problem: wealth inequality.

Because of how the SAT is designed, the test innately favors students from high-income families over their less privileged peers. A quick peek into the College Board’s pricing makes it easy to see why.

As of August 2025, the base fee to register for the SAT is $68, costing $38 more if done after the regular deadline. Switching test centers, canceling an SAT before or after the cancellation deadline, and electronically sending test scores to colleges all tack on extra fees.

All in all, the mountain of costs tied to the SAT means that a student could pay anywhere from $68 to $171 for a single test. Although fee waivers are available for eligible low-income students, offering advantages such as two free tests, not all students qualify. Besides, while these waivers are certainly a step up, they are not enough to prevent rich test-takers from repeatedly outperforming poor ones.

According to CNBC, research indicates that family income remains significantly influential on students’ standardized test scores. Not only can upper-class students afford to retake the SAT multiple times, providing them a better chance of raising their scores, but they also have greater access to private tutors and prep courses—expenses that lower and middle-class households are less likely to cover.

On top of that, wealthier students more often receive additional time on standardized tests, such as the SAT. A 2019 analysis conducted by The Wall Street Journal found that “students in affluent areas” are more likely to secure 504 testing accommodations for conditions including ADHD and anxiety.

Nevertheless, you may be wondering, how much of an effect do these privileges have on students’ SAT scores? The data is incredibly telling.

In a 2023 study conducted by Harvard-based organization Opportunity Insights, and covered by The New York Times, economists found that test-takers in the top 20% of family income were a remarkable seven times as likely to score a 1300 or higher on the SAT compared to test-takers in the bottom 20%. More egregious still, wealthy students in the top 1% of income were 13 times as likely as the bottom 20% to earn such scores.

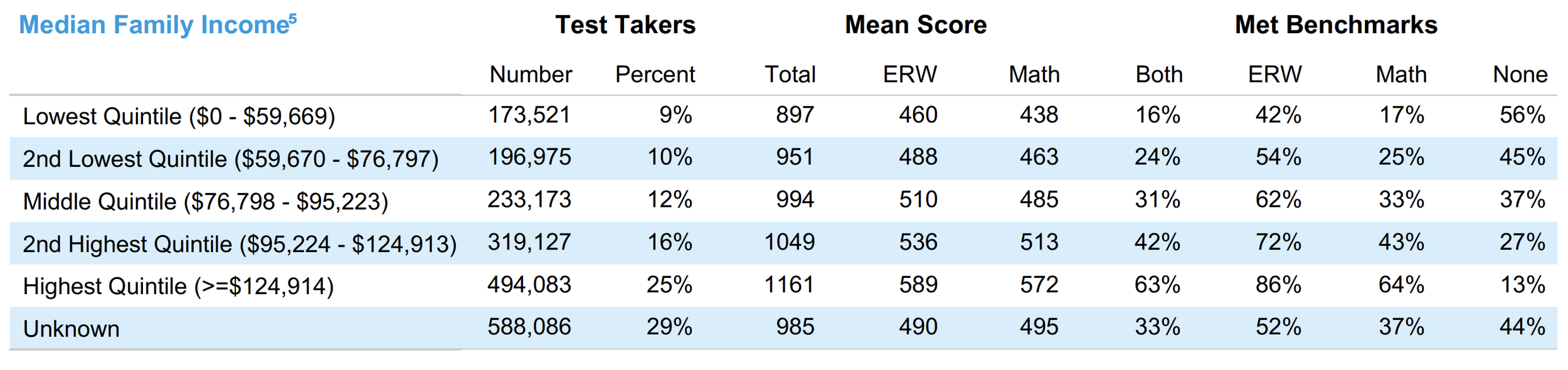

Revisiting data publicized in the College Board’s 2025 SAT report, the wealth gap is easy to spot yet hard to swallow.

Another table from the College Board’s 2025 SAT report displays how test takers of different median family income levels performed. The College Board determined median family income based on averages of regional census data.

Courtesy of the College Board.

Moving from the lowest quintile of family income to the highest, one can observe that students’ average ERW, Math, and overall scores steadily improve without fail. Compared to an overall score of 897 for the bottom 20% and 994 for the middle, test-takers in the top 20% received a mean of 1161. While more than half of the lowest-income students failed to meet the College and Career Readiness Benchmarks, a 63% majority of the highest-income students passed.

As highlighted by The New York Times, income inequality is on the rise in the United States, and the ugly truth is that family income is inextricably tied to race. Therefore, inferring that the SAT is an intrinsically racist test is misguided. Rather, the test’s associated costs hold lower and middle-class students back.

Indeed, for a test so ubiquitously accepted by colleges nationwide, the SAT is riddled with steep, arbitrary fees. Taking a peek behind the curtain reveals that the charges may not be as necessary as they seem.

The College Board is a member organization, composed of 6,000 participating institutions that pay annual fees; it also maintains that it is a “not-for-profit.” As defined by Investopedia, this means that it is an organization established to serve its members and not for the purposes of earning a profit.

Interestingly, as stated by Forbes, the College Board only makes about $2.4 million in revenue from membership payments alone. The vast majority of the organization’s revenue comes from SAT and AP exams. Through mandatory SAT fees and additional charges, the College Board makes a generous $200-300 million every year.

Thus, despite the organization’s self-representation as a not-for-profit, its financial records call into question whether or not the College Board is truly a lucrative monopoly, abusing its power over standardized college entrance testing.

But that’s enough about the test itself. What about the students, seniors, and juniors alike, who take the SAT each year? I set about learning how the Catlin Gabel School (CGS) community felt about the much-debated college test, including their personal experiences and opinions.

Moreover, since CGS is a private, college-preparatory school, I wanted to see how factors such as socioeconomic status played a role in the test-taking habits of its students, myself included.

To do this, I surveyed 60 Upper School students, including 40 seniors and 20 juniors. My survey, which was both random and anonymous, had a solid 78.3% response rate, with 32 seniors and 15 juniors sharing their thoughts.

Of the 32 senior respondents, all but three had taken the SAT at least once. While only two junior respondents had already taken the SAT, each of the others said they planned to take it in the future. Overall, 65.9% of the students I surveyed had taken the SAT before, and more than half had taken it twice or more.

Additionally, 63.8% of respondents had attended prep classes or private tutoring to prepare them for the SAT. While other resources, including free Khan Academy courses and books, were cited as well, the majority of students had access to some form of paid lessons. This came as no surprise, considering my research on wealthy students’ testing advantages.

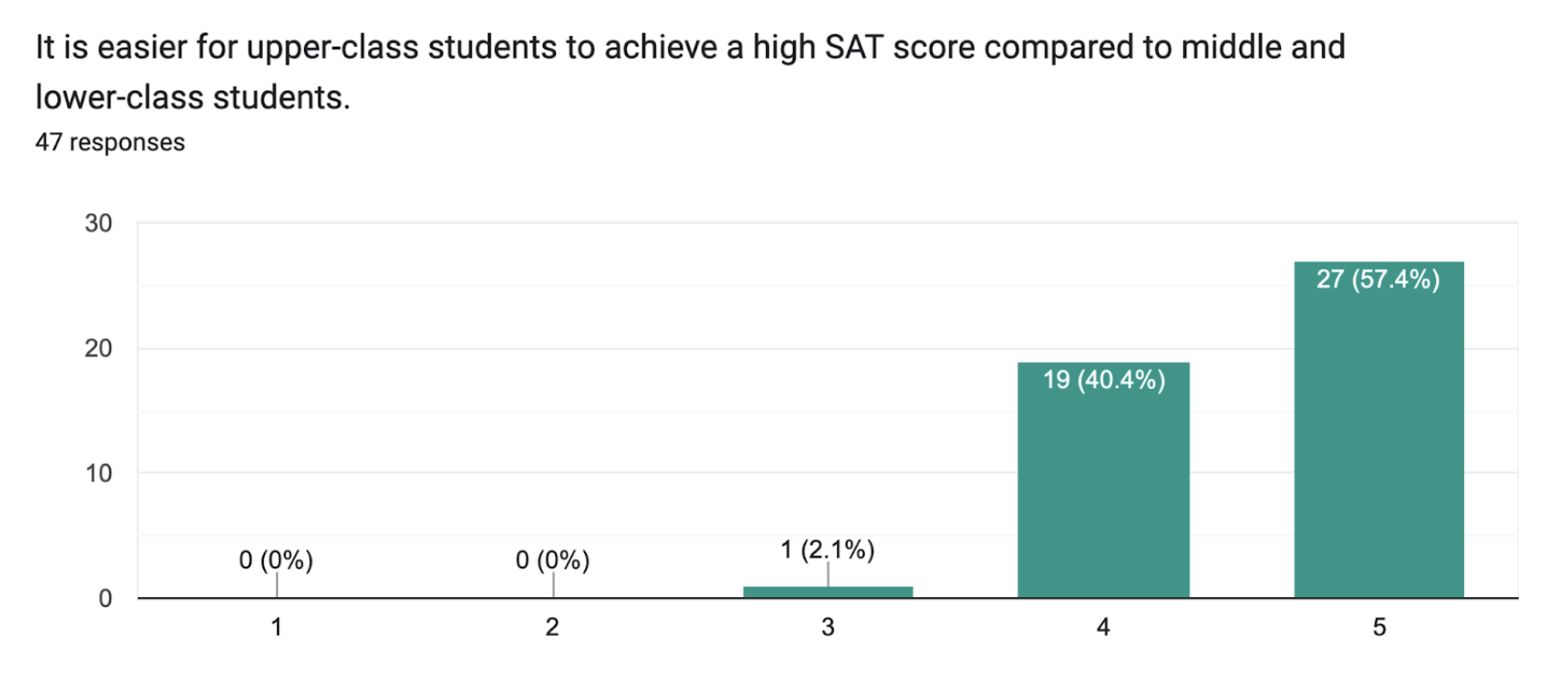

I then asked students to rate their agreement or disagreement with a pair of statements about the SAT. The ratings were out of 5, with 1 representing “Strongly Disagree” and 5 representing “Strongly Agree.”

First, I asked students to rate how much they agreed or disagreed with a statement about the SAT’s dynamics of wealth inequality.

The chart shows whether respondents agreed or disagreed with this statement about how different income test-takers perform on the SAT.

Courtesy of Evan Zhang.

To this question, ratings were heavily skewed to the left, with an overwhelming majority of respondents indicating their agreement. Generally, CGS students were very aware of the invisible leg up that upper-class SAT takers had on their lower-income counterparts.

“Upper-class students will have better access to good education, whether from living in high tax bracket areas with good public schools, going to a private school, or having access to additional materials to study,” emphasized one senior, highlighting the many confounding variables that contribute to the score disparities. Similarly, a different senior spoke to their own experiences involving external help, admitting that “without the tutoring I received, my score would have been way lower.”

Only one junior student had a neutral stance, stating that they “don’t believe tutoring is strictly necessary given the abundance of free online content.” Still, outside of private tutors, wealth allows individuals the freedom to retake the test again and again, an inequity that cannot be overcome simply with free prep materials.

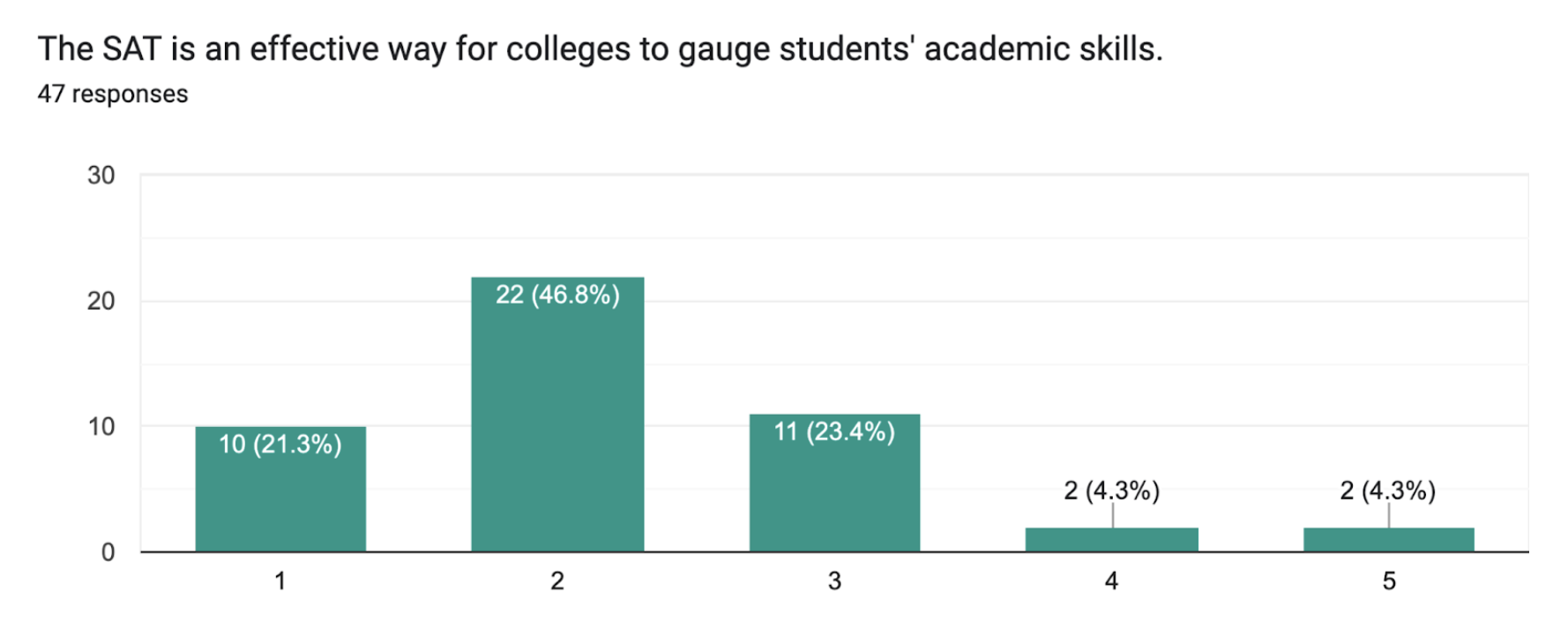

Next, I posed to students the hard-hitting question: Is the SAT effective at measuring academic skill or not?

The chart shows whether respondents agreed or disagreed with this statement about the SAT’s overall effectiveness.

Courtesy of Evan Zhang.

The answer, as the data suggests, was a resounding “no.” More than two-thirds of respondents either slightly or strongly disagreed with the statement, and their reasons were varied yet nuanced.

For instance, one senior lamented that “no artistic ability, no presentation or group work skills, no active class participation or actual writing” was considered at all in the test, limiting the scope and usefulness of a student’s final score. Likewise, another conceded that what the SAT measured could “overlap slightly with work ethic and a basic understanding of grammar and math,” but the test was not a representative diagnosis.

“I think it’s pretty flawed, but it is good at determining a student’s tenacity or thoroughness,” observed a third senior, who put their rating in the middle; they explained that a high score could demonstrate to colleges that a student was hardworking. In a sense, this take is not entirely wrong: for a student who can afford the test, studying hard can pay off. Even so, the perspective overlooks the barriers that tenacious and thorough—but ultimately low-income—students face.

At the end of the day, this is what the problem of the SAT boils down to. It is a test of wealth instead of intelligence, which may be able to capture variations in academic skill among the upper class, but fails detrimentally at fairly assessing students whose family income holds them back. Furthermore, as evidenced by the survey data, individual students question the basic efficacy of the test in achieving its goal.

Already, there has been a cultural shift to acknowledge such shortfalls. The majority of American colleges and universities are moving away from the SAT via test-optional admissions policies. According to The Guardian, researchers are highlighting the importance of GPA as a better measurement of student academics.

But as long as the SAT remains prominent, the College Board’s business model must be amended to target class inequality, rather than focusing solely on the bottom line. The testing agency has to lower prices, not by a little but by a lot, so that retakes are not only possible but guaranteed for all learners.

Otherwise, the SAT will function, as one CGS junior aptly deemed it, much like “a carnival game.” “You can play as many times as you can afford,” not as many times as you like.