A look into the desks of Catlin teachers

By Krish Caulfield ‘26

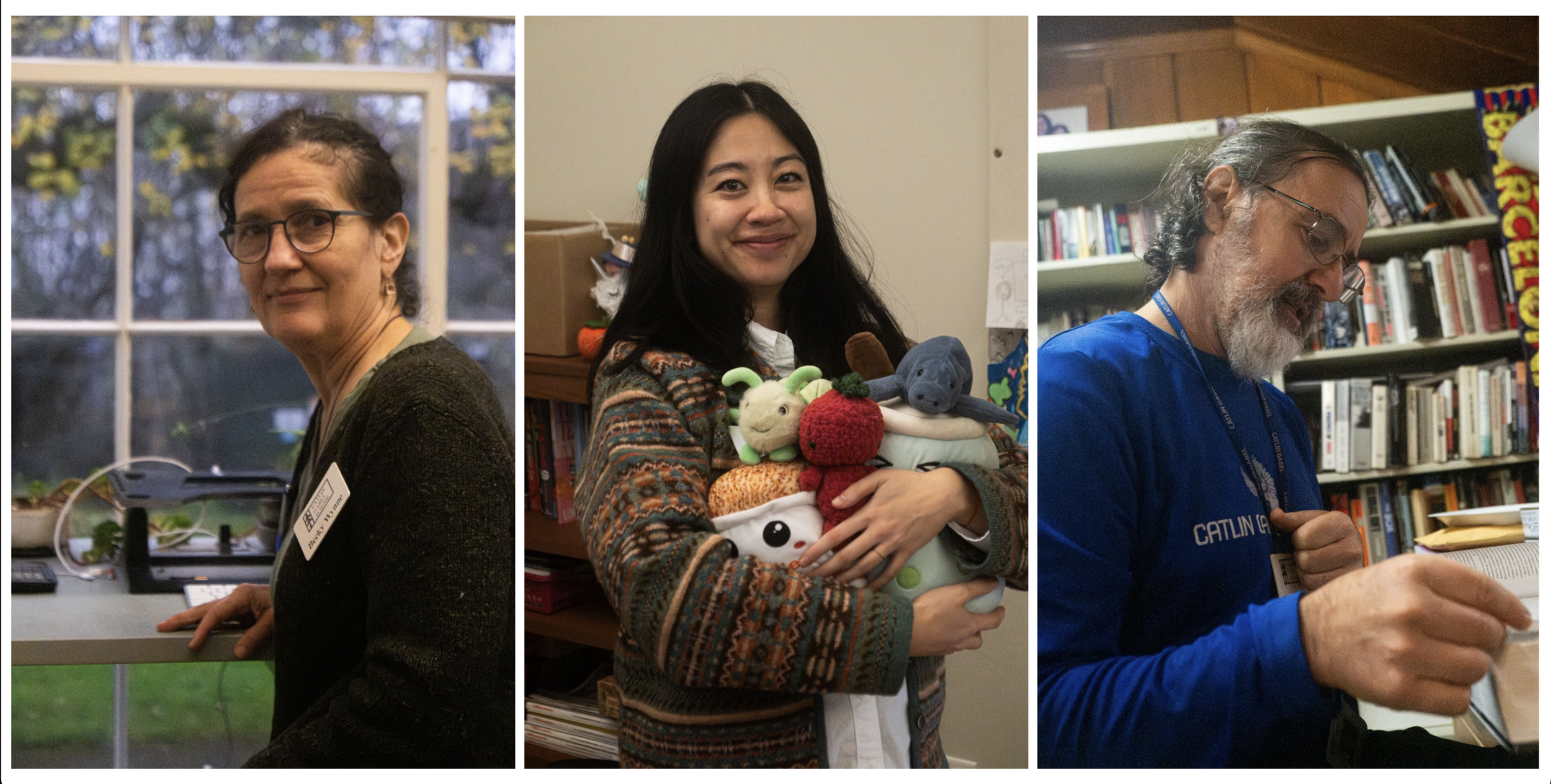

Upper School faculty members Becky Wynne (left), Cristy Vo (center), and Peter Shulman (right) in their offices.

Photos by Krish Caulfield ‘26.

Overcast light punches through the grid of single-paned windows in Darwin, the Upper School science office, illuminating an ecosystem of personal objects: a paper globe colored by decades of travel; a map of Nepal, pierced by thumbtacks that anchor on paper keepsakes and family photos; and a favorite project from a past student. Welcome to the office of Upper School science teacher Becky Wynne (and fellow science teacher Megan McLain).

A moment spent in this office leads to a rather simple realization: everything in here has been lived in or with. Nothing is truly decorative; everything has been handled and shoved aside and dug out again.

Take it from psychologist Sam Gosling, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin, who said in an interview with the BBC that desks “can be so revealing [because] they’re essentially the crystallization of a lot of behavior over time.”

Another psychologist, Lindsay T. Graham of the University of California, Berkeley, described this phenomenon as “behavioral residue” in an article for Berkeley’s Center for the Built Environment. Essentially, physical spaces are evidence of what happens not only within them but also within the lives of the people who occupy them.

This, of course, then begs the question: what actually happens? What does it mean to carve out individual territory, for the sake of productivity, on the Catlin Gabel School (CGS) campus?

Wynne, her desk, and the items—largely related to her family and travels—that surround her.

Photos by Krish Caulfield ‘26.

Wynne’s portion of Darwin is part office, part lab-prep space, part travelogue. The multifaceted nature of her space is a minor miracle in the context of an Upper School where office space is, as she puts it, “very hard to find.” Over a decade ago, Wynne actually shared office space in what is now College Counseling, working in a large communal area—though there were doors—that housed her, a math teacher, and much of the social studies department.

“I actually loved that because I got to hear what the other departments were doing, and that communication piece was really helpful,” she added.

The physical arrangement of teachers and their workspaces, Wynne suggested, shapes how they teach, talk, and prepare. It also shapes what their desks are allowed to be. A teacher whose office is the corner of a constantly occupied classroom cannot spread out and make themselves at home in the same fashion as someone with four walls and a door and a window.

Wynne has spread out into organized chaos. There is a science to that organized chaos, mostly.

Wynne jokingly described her setup as cheating, as she possesses two desks. On one side of her room, under the window, is her teaching desk, covered with stacks of notebooks, notepads, and folders, amongst a scattering of sticky notes. On the other side of Darwin sits the lab-prep desk, which supports the science department's lab exercises.

Off to the side of the two desks, pinned against the wall, shelves climb to a modest height. Yearbooks from every year that Wynne has taught at Catlin pack a lower row. A collection of “random science toys,” fidgets, and puzzles fills the bin on top.

Wynne shared her cribbage set, which she often plays with McLain. Also atop the shelf are many flags from countries that she’s visited, but much of the memorabilia is Nepalese. Wynne described her first trip to the country as “one of the most impactful global trips” that she’s done.

Her office is filled with “random school memorabilia,” she said, but also good reminders. Reminders of life-changing trips and students that she impacted.

When asked whether she actually looks at the stuff, she hesitated. Sometimes “it blends into the background, but sometimes I look at it, and I think of it again.” Wynne and McLain are often too busy looking out their window to notice what’s in their office, as crows, deer, and plenty of other critters wander by frequently, often allured by the peanuts that McLain puts in front of their window.

“I'm very messy,” Wynne said, tidying as she spoke, moving notepads and a stapler and trailing off as she laboriously stacked folders. She, however, knows the other extreme—a barren desk—well.

That extreme was exemplified by former Palma Scholar’s director, Dave Whitson, who would leave his desk completely blank and simply set his laptop on top. A “total minimalist,” in the words of Wynne.

“I have dreams of being a minimalist, but it hasn’t happened,” she added. Nevertheless, what Wynne is doing seems to be working, just as it has for decades.

Across campus, however, another teacher comes closer to living out Wynne’s organizational dreams.

Vo cradling her substantial stuffed animal collection alongside closer looks at some important objects.

Photos by Krish Caulfield ‘26.

Upper School English teacher Cristy Vo is probably at a nearing proficiency-level in terms of her minimalism; her organization, however, is undoubtedly impressive.

Unlike Wynne, Vo does not thrive in chaos. She said she desires solely stacked papers and remarked that she is a “cluttered desk, cluttered mind” person. A lack of clutter, however, does not mean a lack of stories.

Vo’s office is shared with Upper School English teacher Tamara Pellicier and theater director Elizabeth Gibbs on the upper floor of the Dant House. The room has its own lineage, with Vo’s “historic” desk previously occupied by the likes of Liz Harlan-Ferlo, Krystal Wu, and Leanne Moll in the past.

The past is everywhere if you look closely enough.

Above her desk are two class photos from each of the years she taught eighth grade, to the current classes of 2026 and 2027. “I love being at the Upper School, but the Middle School feels like where my family was,” she remarked. Vo likened her coming to the Upper School to entering college and “flying far away from home,” so the photos serve as reminders of that first home as she forges a new one.

There is evidence of that earlier life everywhere: nine red envelopes taped together in commemoration of a Vietnamese and Chinese New Year celebration, a circular wood cookie name tag from Camp Namanu, and plenty of cards from past students.

Vo is also in possession of a robust stuffed animal collection—including a Noodle Lunch cup and boba tea—gifts from colleagues and students, which lives on the shelf behind her desk.

Clinking with South African mugs, from a trip she took to where her husband’s family lives, is a prospering potted plant propagated by Catlin’s own Joey Grissom. She said that all of the items she’s collected—be they plushie or plant—“are all tied to some past student or person.”

Despite the mugs, her desk is largely devoid of content relating to her family or private life. “My family is here,” she joked, before amending her statement, adding that Catlin is “a community that is really important to me.” Either way, her desk reflects that statement; her pinboard and partly-covered but exceptionally organized table illustrate a steady and impressive accumulation of connections.

Upon moving lower, beyond her board and desk, one will find shelves packed with books she has taught in the past and two rather conspicuous bottles of Tajín—one large and one mini—warm with the glow of chili. Vo mentioned, while shaking the bottle, that she often takes the mini Tajín with her in case of an emergency. “It makes fruit taste better!”

Tajín and all, it is clear to see that even in a room with plenty of inherited history, Vo is finding a way to build her own—and log it on walls, on her desk, and on shelves.

Shulman reading in his office amongst a lovely clutter of other books, momentos, and of course, Dolmas.

Photos by Krish Caulfield ‘26.

Out the door and across the way sits Upper School social studies teacher Peter Shulman’s desk, which is, truthfully, more like a controlled landslide. Shulman does his best to keep it contained to his zone, as he shares the office with fellow Upper School social studies teachers Helena Gougeon, Patrick Walsh, and Mickey Del Castillo.

“I try to keep my disaster confined to my own space,” he said before trailing off, “Oh, that’s right, man. This…I was actually looking for this.” Shulman moved his hand to reveal a bulky copy of Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Experience.

Shulman was looking for the book as it belongs to the personal reference library he has constructed both within his office and mind, from which he can pull select texts to help students in assignments. “It's nice to be able to have when a student is doing a research thing … I'm like, great, here's the book,” he said. After walking diagonally from his desk, near the door of the Dant House social studies office, Shulman discussed this internal library.

“These are mine,” he said, fanning a half-pointed finger at the titles. The shelf is packed with content Shulman has used “in teaching classes at one point or another,” with topics ranging from the history of Islam in the West to the Reconstruction era.

The walk back to the “disaster” brings with it greater reflection: there is a layered nature to Shulman’s productive mess. Sure, there are the requisite stacks of books, but there are also recruiting pamphlets and old photos of advisees, there’s a stray plate, coaching gear for the “very developmental” fifth-sixth-grade Catlin basketball team he coaches, and a dry rosemary branch. Somewhere in there is a chess set that belongs to the chess club.

On the bookshelf to the left of his desk, which largely houses Patrick Walsh’s books, lies a family photo and an F.C. Barcelona scarf; Shulman described the club as the “anti-fascist, resistant” to Real Madrid’s “royal” status.

Shulman has not always had this office. He was actually previously stationed in the current College Counseling area alongside Wynne. “We were evicted. It was gentrified. They kicked us out and made it nicer,” he partly joked.

He, too, misses parts of the old arrangement but appreciates the wooden walls and quieter space, even if his “arthritic knee” has to lug him up the Dant House stairs. On some days, he elects to “lock in” within the library, while on others, he can be found at his desk, fishing out a book or grabbing a can of his ever-reliable lunch: Trader Joe’s Dolmas. “If I don’t bring lunch, this is lunch,” he said.

His office-mate, Del Castillo, interjected, “He basically keeps Trader Joe’s afloat.”

Shulman continued enthusiastically, “Dolmas are good things, man. I’m a big fan of Dolmas, for sure,” while brushing fragrant rosemary fragments from his desk. In this landslide, everything he needs remains, somehow, within reach.

Across these three offices—through Wynne’s controlled chaos, Vo’s relatively rigorous organization, and Shulman’s scholarly sprawl—the logic of teachers’ desks begins to become far more evident. Each workspace truly does hold the “behavioral residue” or “the crystallization” of its inhabitant.

That residue is apparent in the yearbooks or flags that Wynne keeps, Vo’s red envelopes or mini Tajín bottle, and Shulman’s dry rosemary sprig or chess set. The crystallizations are evident in mementos from past students and remnants of curricula lost and revised for the better. This is the evidence that unanimously reaffirms their devotion to pedagogy.

A desk can’t teach an Honors Chemistry, English 9, or US History class, but it does a fine job of showing us who does.